Healthy Futures: Why “Access” to Healthcare is Not Enough for Good Health Outcomes

By Vijay Wadhawan

Vice President Health and Wellness -

Environics Research

When health care appears in entertainment, it’s usually in the form of a dramatic intervention: an emergency surgery or a med-evac helicopter flight. But in real life, it’s the simple, upstream steps where the most important action happens. Low-cost, low-drama factors like regular visits to family doctors and effective day-to-day management of chronic conditions make an enormous difference in the lives of patients and in the success of health systems.

For Canadian proponents of quiet but powerful early interventions in health, a recent study from the IRIS Research Network brought good news. IRIS carried out a

Global Economic Confidence Survey in 2019; Environics led the study in Canada, joining 23 research partners in countries across Europe, Asia, and the Americas. Across all the countries surveyed, 32% of residents reported that their current economic situation prevented them from accessing a medical service or doctor’s visit. Within North America, that figure was 26%. But the share of Canadians who said that financial considerations kept them away from some form of care was significantly lower: 12%.

That proportion may be 12 points too high for many advocates but it does indicate that the vast majority of Canadians, including plenty of folks with lower incomes, feel unconstrained by their finances when they consider checking in with a healthcare provider. Three-quarters of Canadians (77%) say they get regular medical check-ups, even when they’re feeling fine.

These are all promising signs about Canadians’ understanding of their access, at no direct cost, to primary care. But financial concerns are not the only ones that affect people’s likelihood of seeking care. Social values – the way people see institutions, science and technology, and other important concepts – also have a powerful influence on health choices and behaviours.

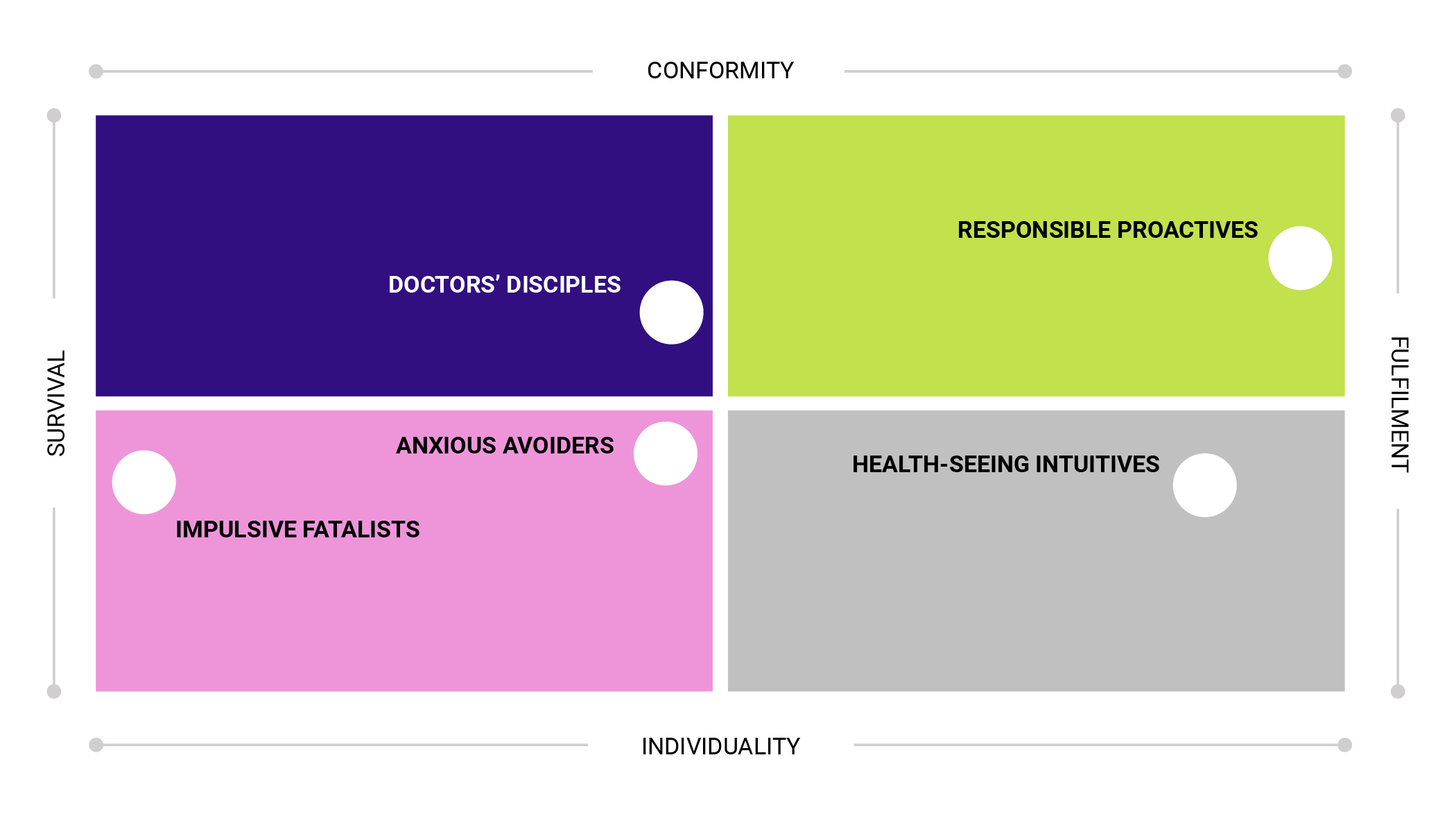

As part of our long-running social values research program, Environics has grouped Canadians into

five health value-based segments. When we look at the share of each of these segments who seek regular medical check-ups even when they feel fine, we see notable differences from the national average of 77% introduced above.

A group we’ve labelled the Responsible Proactives are the most likely to get regular check-ups. As their name suggests, these Canadians don’t wait for something to go wrong: they do what they can to prevent health issues before they arise, and 83% of them say they visit a doctor regularly – seven points above the national average.

At the other end of the spectrum are the Anxious Avoiders. These folks feel overwhelmed by the pace of change and the complexity of life, and this generalized anxiety affects their orientation to their own health. They have little faith that their own choices and behaviours can make a meaningful difference, so it’s perhaps not surprising that only about six in ten Anxious Avoiders (61%) seek regular check-ups.

It’s worth noting a second segment of Canadians who are less likely than average to have regular doctors’ visits, but for very different reasons. About two-thirds (66%) of Health-Seeking Intuitives get regular check-ups. But whereas the Anxious Avoiders skip the doctor because they feel little control over their health, Health-Seeking Intuitives feel comfortable taking their health in their own hands, trusting their own judgment (often taking a holistic approach) and questioning mainstream medical authority.

This brief look at how patients’ social values intersect with their likelihood of getting regular check-ups suggests that having access to a primary care physician at little or no cost may not be enough to get Canadians in the door for regular, preventive care. A host of non-financial factors inform people’s choices about whether to make use of the care that’s available to them. Importantly, Canadians with some chronic diseases, such as diabetes, are overrepresented in the patient segments that are less likely than average to seek regular check-ups with a doctor.

For health leaders whose goal is to promote the wise and effective use of health system resources, it’s vital to understand the motivations, assumptions, and fears that can make Canadians more or less likely to proactively seek routine care. The greatest potential for better outcomes for patients and systems is at the intersection of access and education. Canadians can benefit from being better informed about the importance of their personal role in their own health care, including how to get the most out of their access to physicians. The most effective informational messages will align with Canadians’ values.

Dramatic, high-cost interventions are exciting on TV – but in the real world, they’re a tiny part of the work that saves and improves lives. Many Canadians might be surprised to learn just how much their own choices and actions can shape their own health and the efficacy of the health systems they rely on.