Fairer Economies: Why Social Mobility in Canada Depends on Building More Housing

By David MacDonald

Group Vice President of Financial Services -

Environics Research

The promise of social mobility is at the heart of free societies: it presumes that the circumstances one is born into as a child will not necessarily dictate where one winds up later in life. It’s important for social cohesion that talented children born into families with limited means be given the opportunity to succeed, and that the offspring of the rich are not given a free ride into prosperity. Without the promise of social mobility, individual citizens lose important opportunities and motivations to strive, and collectively citizens risk becoming powerless subjects under a permanent, hereditary ruling class.

How does Canada stack up compared to other developed nations in terms of social mobility? Recent data from a range of sources offer some insight, and give some clues as to the factors that support and threaten our ability to sustain a flexible, mobile society.

The

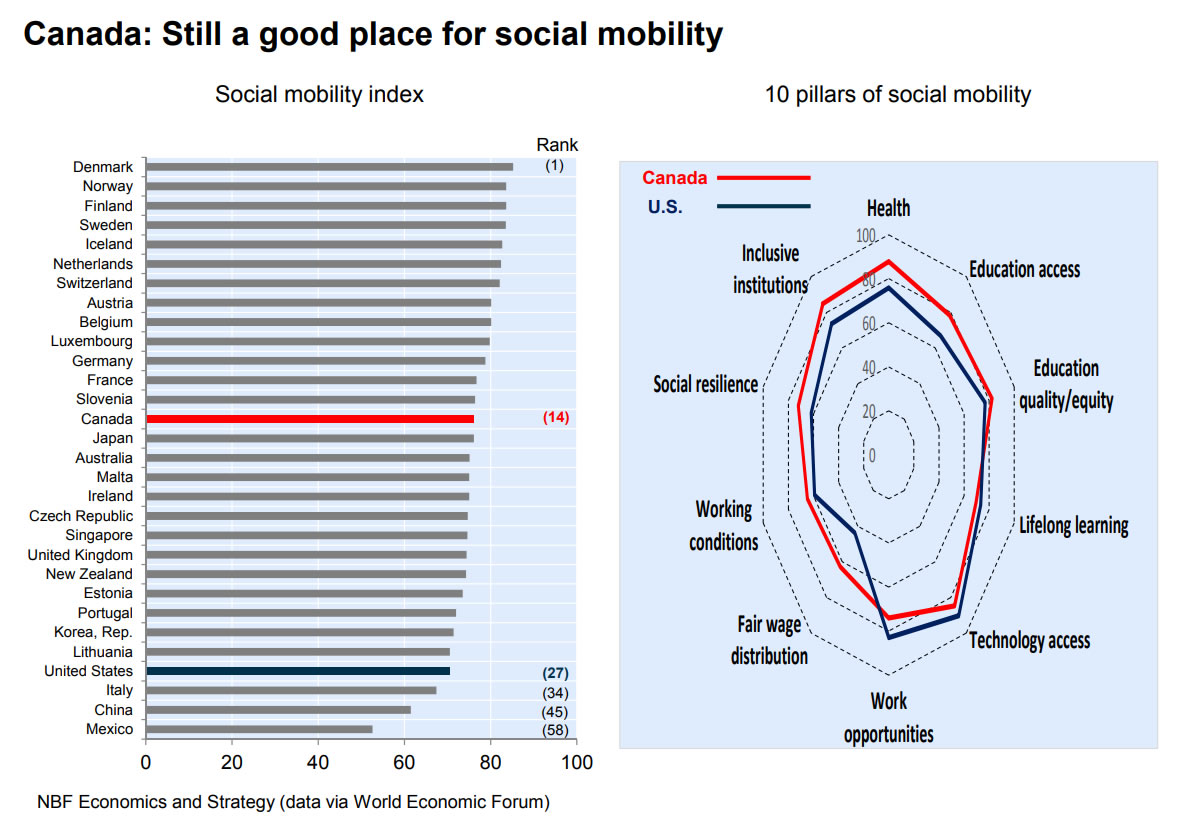

Global Social Mobility Report 2020, released recently by the World Economic Forum (WEF), ranks 82 nations on social mobility. Denmark ranks first, followed by other Nordic countries. The United States ranks 27th while Canada ranks midway between these countries, in 14th place. In fact, Canada is the highest ranked country outside of Western Europe. We’re tied with Japan, and somewhat ahead of Australia, Malta, and Singapore.

The WEF report ranks countries according to a composite scale based on 10 categories of inputs, including health factors, education access, working conditions, and social protections. The report notes that Canada performs well on many of these categories, notably health, technology access, and education quality and equity. We fall short in the “fair wages” category, as a result of low pay among workers and unemployment among workers with lower levels of education.

Canada often compares itself to America on a wide range of social and economic characteristics. A

spiderweb created by National Bank provides a graphic illustrating how Canada and the United States line up on the WEF dimensions. The graphic shows at a glance that Canada exceeds the US on most dimensions, particularly Fair Wage Distribution, Health, Education, Inclusive Institutions, and Social Protections. Where we lag the US is in terms of Work Opportunities, Technology Access and Life Long Learning, the latter of which include gaps in the extent of staff training, active labour market policies, and digital skills among the active population. These findings are not surprising, given that Canada has traditionally had a more active government – hence the positive health and education outcomes – while the United States has been known for an extraordinarily dynamic economy.

One result of these differences is that America’s economy, where winners win big, begets more severe inequality. The Gini ratio, a critical measure of income inequality, shows that Canada ranks midway between OECD countries with the least income inequality (Finland, Norway, Denmark, and Sweden) and the United States, which is much more unequal.

Unfortunately for Canadians, the countries at both ends of the inequality spectrum outperform Canada economically. Our GDP per capita lags both the Nordic countries as a bloc and the United States. Canadian business productivity has long been a concern, and the recent

Global Economic Confidence Study by Environics Research and our IRIS partners shows that Canadians exhibit weaker consumer confidence than Americans (only 59% of Canadians vs. 67% of Americans think it is a good time to buy the things they want and need) and more are worried the economy will worsen in the coming months (44% vs. 26%). Environics Research’s own

social values research further shows that compared to this time a year ago, Canadians are less likely to say that their financial position is more secure (19% vs. 27%), and more likely to say it has become less secure (29% vs. 23%).

Missing from all of this research are metrics related to the cost of living. In Canada, the cost of living is powerfully driven by the cost of housing, which we can expect to impact social mobility for years to come. A myriad of factors drive real estate markets, but in Canada the fundamentals of demand outstripping supply for many years has resulted in rapidly rising home prices in our largest urban centres, most notably Vancouver and Toronto. The Greater Toronto Area (GTA) has seen some 40,000 new housing starts per year over the past 3 years, but this output has not kept pace with the population growth of approximately 160,000 per year over the same period.

Over the past four years,

Environics Research has conducted bi-annual surveys of first-time homebuyers for Genworth Canada, a leading provider of mortgage insurance for those making down payments of less than 20% on their homes. Our last survey in 2019 showed the impact of rising home prices and more restrictive mortgage qualification requirements imposed by the Federal Government to curb rising home prices. In our surveys the proportion of 25 to 40-year-olds who bought their first home in the prior two years was cut in half, from 11% in 2015 to just 5% in 2019. Moreover, as home prices rose through this period, the proportion receiving financial help from their parents or other family members and friends jumped from 31% to 37%. Those receiving such gifts are more likely to live in the most expensive markets in the country, and these additional funds allowed them to buy more expensive homes than those who did not receive such support. The well-intentioned benefactors at the “bank of mom and dad,” who are individually wanting to help their adult children get launched and start families of their own, are collectively fueling further home price inflation in these markets. This in turn makes home ownership less affordable to those born outside of these more affluent families, thereby threatening to worsen future social mobility in Canada.

Some are counting on Boomers to free up supply by vacating their urban homes and downsizing to smaller communities to help fund their retirements. However, more ambitious solutions involving urban intensification, brownfield developments, mixed use zoning laws and government-funded, purpose built rental properties will be required. It is clear that solutions to housing affordability will not come easily, but must be undertaken not just to help young Canadian families today, but to ensure the promise of social mobility for future generations.